In considering vehicle purchasing or leasing, some considerations that are front of mind include vehicle fit-for-purpose – can it do the job – total cost of ownership, upfront costs and added complexities. Typically a fleet manager will develop a fleet policy in conjunction with the broader organisation, that addresses minimum fit-for-purpose requirements, including [1]:

- Meeting five-star ANCAP safety rating;

- Availability ‘up-time’;

- Providing value for money; and

- Addressing environmental considerations.

Beyond this high-level detail, it is the role of Line Area Managers or Procurement Managers to fill-in the fit-for-purpose gaps and make a judgement call on a suitable vehicle choice. Next level considerations might include:

- Number of passengers;

- Volume, size and weight of typical cargo;

- Towing requirements; and

- Appropriateness for comfortable long-distance travel.

For example:

Consider an urban council with pool vehicles making up part of their fleet. These vehicles are used by Council staff for day-to-day operations, with the average pool vehicle traveling less than 70km per day. The vehicles return to Council buildings after completing their daily journey, and are parked on Council land in designated parking spots.

Consider that the fleet policy outlines fit-for-purpose considerations as per those outlined above, and that the conditions of use for a pool vehicle include:

- Pool vehicles are not to be used for private purposes. Bookings will only be accepted where the use is 100% business travel.

- Pool cars (i.e. sedans/wagons/hatch) are not permitted to be used for interstate travel.

- All pool wagons are fitted with cargo barriers. Requests to reconfigure the cargo barrier to allow folding down of the rear seats must be made at the time of vehicle booking.

- All cargo must be stored in the boot or behind the cargo barrier (this includes luggage and laptops).

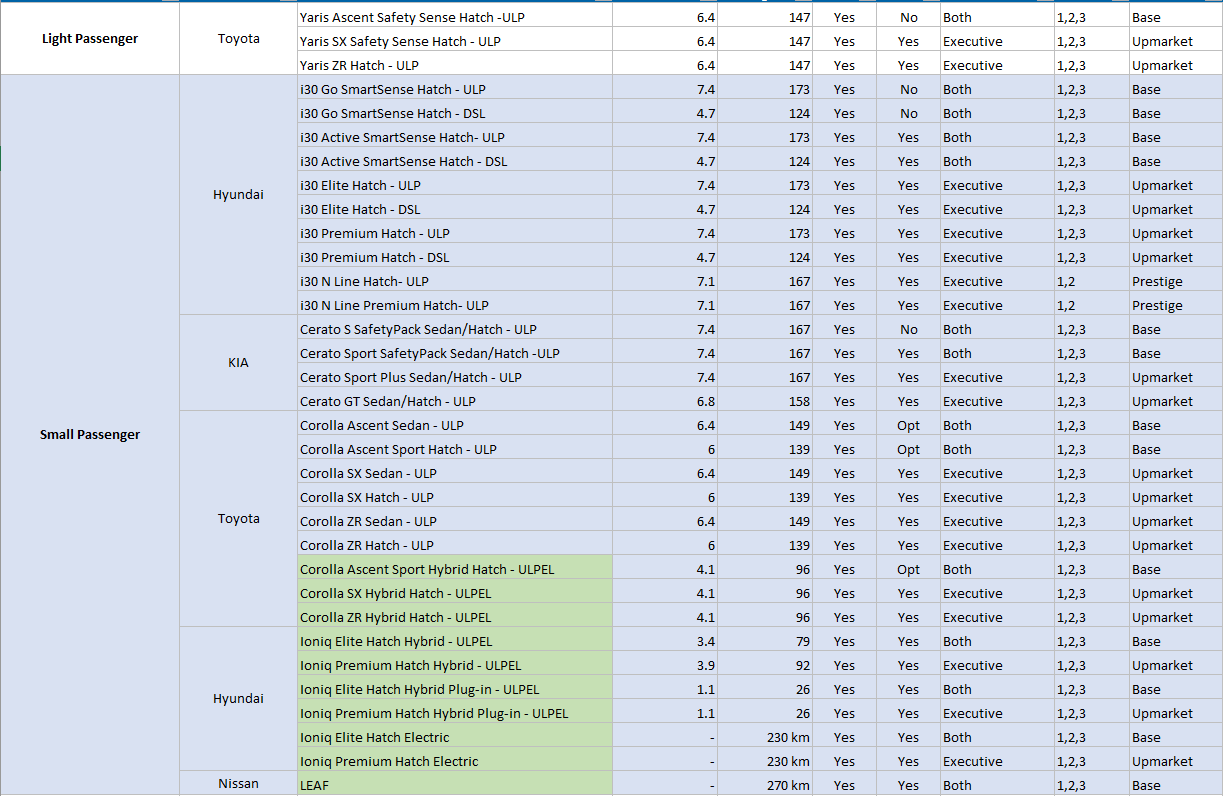

Given the minimum requirements of the council pool vehicle fleet policy, the Fleet Manager will weigh-up fit-for-purpose criteria and feedback from the relevant line area. In this example, the Fleet Manager notes the low daily travel distances and a low typical passenger and cargo carrying requirements and determines that a small passenger vehicle will satisfy fit-for-purpose requirements. The Fleet Manager then seeks to procure a vehicle from the approved vehicle list matching the ‘small passenger vehicle’ category determined [2]:

An example of an approved vehicle list

The EV case has to be on the table

It may be surprising, but considering EVs as potential fleet vehicle candidates works in just the same way, with EVs often scoring very highly as quiet, comfortable and boasting a low total cost of ownership.

This is important.

We know that Australia’s small passenger EV market is still growing in the number of options available, and that the upfront costs of electric vehicles are higher than their petrol/diesel size-equivalents. This doesn’t mean however, that EVs should not be included on approved vehicle lists, as their low running costs often make them a strong cost-based candidate even before the other benefits of EV driving are considered. The above table form the VicFleet approved vehicles list for example includes electric vehicles (including HEVs, BEVs and PHEVs).

Example A – Comparing an EV:

When comparing electric vehicles and petrol/diesel equivalents, it is still important to compare vehicles in the same category, so that the facts stack up.

Consider that the example council studies this like-for-like comparison:

- Hyundai i30 Elite Hatch – Petrol; and

- Hyundai Ioniq Elite Hatch Electric.

Both of these options are small passenger vehicles with similar passenger and cargo carrying capacity, they are similar in size, and they are similar in performance. Comparing these two vehicles means an accurate total cost ownership measurement can be made.

Example B – Comparing an EV

Consider the case, however, if the council in this example had compared the following vehicles:

- Hyundai i30 Elite Hatch – Petrol; and

- Tesla Model X.

In this comparison, the total cost of ownership comparison would show a strong bias towards the petrol vehicle. Importantly, this is not a direct measure of like-for-like performance, as the Tesla is an upper-large sized premium SUV, whereas the Hyundai is a small, non-premium sedan.

Results:

For pool vehicles in this example, the council identifies an appropriate like-for-like comparison (Example A) and uses the BetterFleet total cost of ownership tool to compare the total cost of ownership. The tool demonstrates that over the annual distance travelled by the pool vehicles, they can replace their existing small passenger vehicles with fully electric Hyundai Ioniq’s and actually save money in doing it.

–

The aim of the Charge Together Fleets program is to help fleet and sustainability managers consider electric vehicles in their fleets by measuring them on total cost of ownership. The BetterFleet tool helps you do this.

–

We have compiled this table to help you compare like-for-like vehicles.